Emerging leaders for our lakes

About the author: My name is Karin Swanson and I am a student of the Yahara Watershed Academy. I work for Clean Lakes Alliance as the Marketing and Communications Associate Manager and I am a Meteorologist. I am sharing my journey through the Academy in an effort to expand our community’s knowledge and passion for the Yahara River Watershed.

The third class of the Yahara Watershed Academy took place on April 10th at Edgewood College in Madison. There are five day-long classes included in the Academy before the June graduation. Students have been learning about the science and history of the Yahara River Watershed, while being mentored by local leaders.

A cohort of 25 students makes up the 2019 Yahara Watershed Academy. The Academy involves a partnership with the University of Wisconsin-Madison Nelson Institute for Environmental Studies and Edgewood College. By graduation, students will have received the knowledge and skills to become a network of informed leaders for our watershed.

The third day of instruction began with a leadership panel made up of five area leaders, including:

- James Tye – Founder and Executive Director of Clean Lakes Alliance

- Jessie Lerner – Former Executive Director of Sustain Dane, Coordinator of the MPowering Madison Campaign

- Paul Robbins – Dean of the University of Wisconsin-Madison Nelson Institute for Environmental Studies

- Mike Strigel – President and Executive Director of Aldo Leopold Nature Center

- Steve Gilchrist – Program Director of the Social Innovation and Sustainability Leadership Graduate Program at Edgewood College

James Tye, Jessie Lerner, Paul Robbins, Mike Strigel, Steve Gilchrist (Left to Right)

The importance of partnerships

The leadership panel discussed the value of partnerships. James Tye discussed how working with other leaders helped him develop the nonprofit, Clean Lakes Alliance. He said when you start a project, you need to lay the foundation first by talking to a lot of people about the project and getting everyone involved from the ground up. This method will allow everyone to feel involved and have a stake in the plan so it can become a collaboration.

Paul Robbins discussed the importance of not just having a partnership, but using that partner’s knowledge to the full extent.

“Don’t just honor what your partners want, honor what they know.”

Paul Robbins, UW Nelson Institute

Career takeaways

The leadership panel discussed past failures and how they have learned and evolved as leaders based on those failures. Without failures along the way, it’s tough to become successful. Mike Strigel says it’s important to take risks in life and make mistakes, then learn from those mistakes so you don’t make them again.

Jessie Lerner explained about the importance of leveraging influence, no matter what.

“You can be a leader no matter what. It doesn’t matter your sphere of influence. All of us, no matter where we are, can create change and be influential.”

Jessie Lerner, Sustain Dane

Failure can be important

Communication is one of the biggest factors in success or failure. Having a good communication strategy from the beginning of a project can save time and money in the long term. Jessie Lerner described a past partnership and how she evolved and learned from it.

“Sit down initially to communicate and discuss the outcome of the project. Even if you don’t think you have the time, it’s better to spend the time developing a functioning partnership rather than cleaning it up later.”

Jessie Lerner, Sustain Dane

Steve Gilchrist explained that conflict will occur. The important thing to remember is to use the conflict constructively.

“Develop a sense of trust. Support each other even if mistakes are made. Create a space in the organization so that people can learn and change based on mistakes.”

Steve Gilchrist, Edgewood College

It can be difficult to discuss success

The leadership panel had plenty of failures to talk about, but when asked about their successes, each leader became reflective. The panel decided that sometimes it can be more difficult to talk about success. However, everyone seemed to agree on a few key points:

- Every success is made up of many failures.

- Try to look at the situation and figure out what were the best ideas in the project. No egos!

- Be persistent, and be flexible.

- Continue to learn.

- Be aware of your strengths and weaknesses.

“Clean Lakes Alliance is successful because we have built such a diverse and dynamic team. I need to listen to everyone. Build a team with people who think and work differently and then get them to work together.”

James Tye, Clean Lakes Alliance

“Be persistent. Be flexible to adapt and go where the energy is going.”

Steve Gilchrist, Edgewood College

The final part of the leadership discussion included an exercise among students to discuss two topics.

Small group discussion topics

- Identify a great leader the student knows personally and explain why that person is a great leader.

- What role(s) as a leader has the student assumed in life – perhaps not even realizing it at the time? In assuming a leadership role, what challenges has the student faced and perhaps overcome?

The small group discussion was quite intriguing to me, as a student, because the leaders our group discussed likely had no idea they would be thought of as a leader. The discussion centered around people who were simply going about their work and life trying to be supportive and kind to others.

Badger Volunteers

Badger Volunteers is a program that pairs University of Wisconsin-Madison students with community organizations such as nonprofits, schools, and municipalities. The students volunteer for one to four hours per week at the same organization. Reuben Sanon coordinates the day-to-day operations of the Badger Volunteers program. He works closely with students to match them to the correct volunteer opportunity.

“Your role as a leader is not to know everything. You should know your team’s strengths so they can get things accomplished.

Reuben Sanon, Badger Volunteers

Sanon discussed the UW Leadership Framework and its use in the Badger Volunteers program. The framework is not based on position or authority level, but demonstrates how every situation is unique and comes with a different context. It’s based on three main values, and seven competencies.

Stormwater management on Edgewood Campus

Jim Lorman worked at Edgewood College for close to 30 years, and has been invested in our lakes through Friends of Lake Wingra and the Dane County Lakes and Watershed Commission. Lorman gave the Yahara Watershed Academy a tour of the Edgewood Campus and its stormwater management design.

The stormwater design was developed around 20 years ago, and at the time, it was considered to be state of the art. The campus design includes a stormwater retention pond, which are required in many new developments. However, when the pond was installed at Edgewood College two decades ago, it was somewhat unique to be included in the design plan.

The stormwater retention pond works to minimize flooding. It’s a pond that doesn’t infiltrate, meaning it fills with runoff and sediments, but the water does not infiltrate into the ground because it has a liner. The liner on the bottom keeps the sometimes toxic sediments from reaching nearby Lake Wingra.

Lorman also took Academy students to see various berms and rain gardens that had been developed throughout the campus. A grass swale is between Edgewood College and Edgewood School. It took a lot of work to create the swale, and has undergone changes throughout the years that have not always been positive. A recent restoration of the grass swale now allows the area to mitigate runoff and increase infiltration. Another bonus – it has become a wonderful bee and butterfly habitat!

Native American mounds of Edgewood Campus

Larry Johns is a member of the Oneida Tribe. He is dedicated to preserving Native American burial mounds and other sacred sites. He has been surveying burial mounds in Dane County since the 1980s. In 1986, a law to protect American Indian burial sites passed in Wisconsin. Many sites have been destroyed through the years, but if you look closely, you may notice some still intact throughout the Madison area.

Johns took the Yahara Watershed Academy on a tour of the burial mounds located on the Edgewood Campus. It can be incredibly difficult to find burial mounds unless you know exactly where to look. There are some old maps that show approximations of some of our local mounds. One map was published in a book by Increase Lapham in 1855. The book contains the first maps of Wisconsin, but may not be incredibly accurate with the position of the mounds.

A second map Johns uses as a reference comes from A.B. Stout and his 1906 land survey of the Edgewood Campus area. It shows the approximate placement and shape of some of the burial mounds on the campus.

When Johns surveys burial mounds, he looks for various clues about their placement. He looks for “grandfather rocks” – rocks left behind by the glaciers. Johns looks at the rocks and their position to the trees to determine where a mound may be located.

Mounds hidden in plain sight

There are three mounds along one of the main paths on Edgewood Campus. One of the mounds is not in good shape, but the other two have had less damage through the years. There is another mound closer to the lake called the “Panther Mound.” This mound represents the water spirit and points toward Lake Wingra. However, this mound is a bit confusing to Johns. Although the shape and direction are reflective of this type of mound, its composition is atypical. A tree had overturned near the mound, allowing some of the mound composition to become visible. There were rocks and clay showing, which is unusual. Sediment or soil often makes up mounds rather than small rock.

Johns explained that when Native Americans made burial mounds, they would dig one or two feet down into the soil. They would place bodies and objects inside the carefully planned burial site and then add sediment or fill from elsewhere. The origination of the sediment that filled the mounds is one of the mysteries scientists and mound surveyors are still learning about.

Charles E. Brown also mapped the mounds of the Edgewood Campus area and similar to Stout, mapped a dotted line of mounds along the shore of Lake Wingra. Many of these mounds are still standing, however some are likely eroding faster than they should – perhaps from runoff or wind.

History of Yahara Watershed and its people

Missy Tracy is the Municipal Relations Coordinator at Ho-Chunk Gaming. She spoke to the Yahara Watershed Academy about local Ho-Chunk history and land ethic in Wisconsin. Tracy’s Ho-Chunk ancestors first arrived on the lands of what is now Wisconsin more than 10,000 years ago.

Omar Poler is a member of the Sokaogon Chippewa Tribe of northern Wisconsin and is an Outreach Specialist with the UW School of Education. Poler’s focus is on teaching and communicating about Wisconsin’s Native American history.

Tracy and Poler spoke about the importance of recognizing and learning about the Native American history of the Yahara Watershed. There are links between the area’s past, present, and future. Much of the Native American history is passed down orally. So how can we work these ideas and teachings into children’s school history? How might we be different if we understood the stories of the Ho-Chunk and American Indian people? Wisconsinites celebrate Aldo Leopold. Why not celebrate indigenous people and connect people with the place we call home?

Madison as a world heritage site

Madison has hundreds of mounds around its lakes. Mounds exist on Park Street, Monroe Street, throughout the University of Wisconsin-Madison campus, at Olbrich Botanical Gardens, and the list goes on from there. “Madison is a world heritage site of mounds,” said Poler. He questioned, “If we saw Madison as a true heritage site, how might we care for it?”

Recommended reading about the Native American and indigenous people of Wisconsin.

- Charles E. Brown papers

- Paul Radin – The Winnebago Tribe

- Bob Birmingham – Spirits of Earth

Health impacts of pollutants in the watershed

The final speaker of the April Yahara Watershed Academy was Dr. Claire Gervais with the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health. She is also a founder of the nonprofit, Healthy Lawn Team, and works on the Meadowood Health Partnership to bring health care and healthy food to the Meadowood neighborhood. Dr. Gervais’ focus is on the health impacts of pesticides and PFAS.

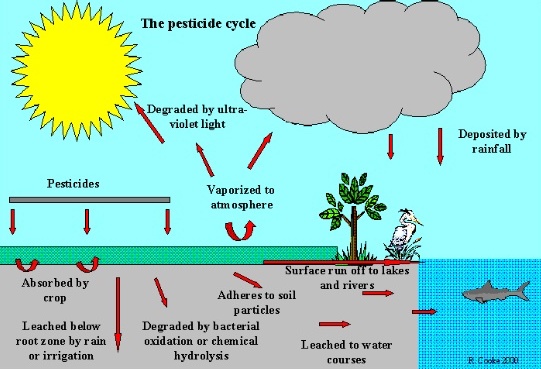

Pesticide exposure

There are several types of pesticides, including herbicides, insecticides, fungicides, rodenticides, and antimicrobials. Exposure to pesticides occurs through contact with elements like water, lawns, and air. Doctors and scientists are continuing to learn about the effects of pesticides on our bodies. One thing is for certain, children and babies have a higher risk of chemical exposure due to their small size, developing organs, skin exposure, and hand to mouth activities.

About one-third of private wells in Wisconsin have pesticide contamination. The use of some pesticides, such as atrazine, is now dropping because of newer Wisconsin laws regarding their use. City and state governments have been recognizing the impact of pesticides on people and have made some changes accordingly. For instance, Madison Parks has been working with volunteers to pull weeds rather than using pesticides in some of our local parks.

PFAS

PFAS have become a frequent topic in the news recently. The acronym refers to per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances that enter waterways and don’t break down. They originate from firefighting foams and from chemicals used in non-stick cookware, water-resistant clothing, and stain-resistant furniture, as well as other sources.

PFAS can be found in lakes, rivers, and in drinking water. Because the substance doesn’t break down, it can become a traveling plume of chemicals. PFAS cannot be removed from our water with carbon filters or other filtering methods used by water utility departments, and are therefore being ingested by people.

Dr. Gervais said there are currently no environmental standards in Wisconsin or in the United States for PFAS. Of the more the 11,000 public drinking water systems tested in Wisconsin, only about 90 have been tested for the chemical. Because scientists are still learning about PFAS, Dr. Gervais recommends going to the PFAS Community Campaign on Facebook and liking their page. She also recommends the information on the Midwest Environmental Justice Organization website.

Additional pesticide resources

- Beyond Pesticides

- Pesticide Fact Sheet from Northwest Center for Alternatives to Pesticides

- Citizens for Safe Water Around Badger

This month’s Yahara Watershed Academy included a great deal of information that needed to be absorbed and reflected upon. Even now, as I finish writing this article, I am thinking about the people who once inhabited the Yahara Watershed hundreds, and even thousands of years ago. I am reflective about their story and their oftentimes unnoticed value to this region. I believe that as people learn more about their past, they can make better decisions and choices for the future.

Read more about the Yahara Watershed Academy