The brisk air is a reminder that our local lakes will soon freeze, but predicting when is anyone’s guess. There is a complex interplay of many forces that uniquely influences each lake’s ice-on date. (Learn more about the Mendota Freeze Contest and make your guess for when Lake Mendota will freeze.)

Freezing air temperatures are obviously the driving force behind lake ice formation. Yet water has a high specific heat capacity. This means it takes a lot of energy to change the temperature of water compared to other materials. Therefore, air temperatures from much earlier in the season can impact timing of ice formation. A cool September, for instance, can set the stage for an earlier freeze.

Wind also plays a role. Ice forms slowly as water molecules bind into a growing ice crystal. Wind produces waves and water movement, hindering the molecule’s ability to bind at the surface even when water temperatures are below 32 degrees. Lakes with a large surface area can be greatly impacted by wind. Similarly, water movement from flowing rivers and currents can also hinder ice growth on a lake due to the same process that hinders crystallization.

Besides weather, the unique hydrology of each individual lake also greatly influences the timing of ice formation. Deeper lakes with a high volume-to-surface area ratio will cool more slowly and tend to freeze later. Shallow, wide lakes can more efficiently dissipate heat and often freeze sooner. Spring-fed lakes, supplied by roughly 52-degree-Fahrenheit groundwater, can have significantly later freeze dates compared to lakes with minimal groundwater inputs.

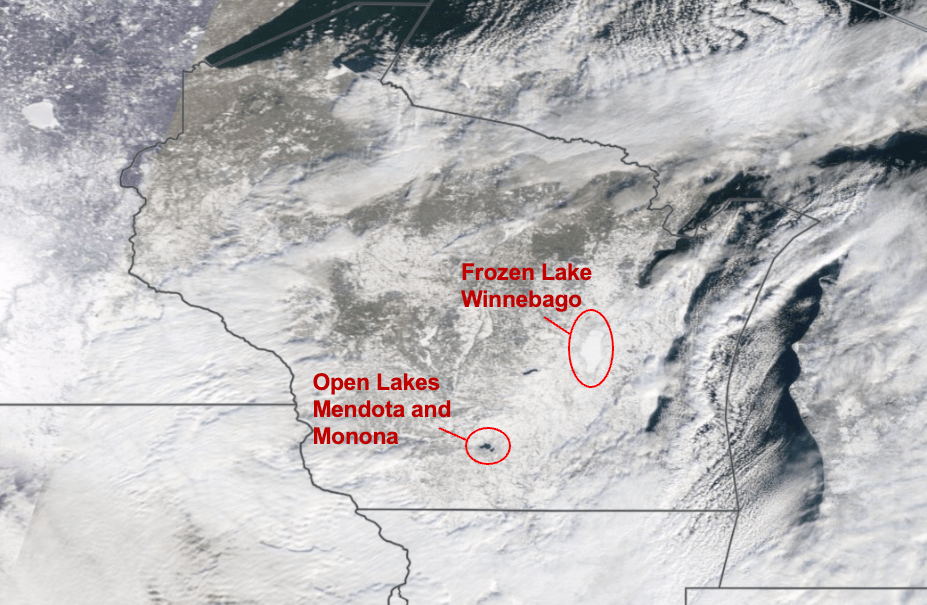

These factors help explain why freeze dates can vary so widely. Lake Winnebago, for example, often freezes before Lake Mendota (as shown in the satellite image above from December 20, 2024). While being a much larger lake by surface area to the north, Lake Winnebago is a relatively shallow lake with a mean depth of 15.5 feet. Lake Mendota, on the other hand, has a mean depth of 45 feet. This allows it to remain warmer later into the cold winter season. In general, large, deep, and predominantly groundwater-fed lakes will freeze later than shallow, wide, or small lakes.

Article written by Mike Smale, Clean Lakes Alliance Watershed Programs Specialist