Growing a new group of lake leaders

About the author: My name is Karin Swanson and I am a student of the Yahara Watershed Academy. I work for Clean Lakes Alliance as the Marketing and Communications Associate Manager and I am a meteorologist. I will bring you along on my journey through the Academy in an effort to expand our community’s knowledge and passion for the Yahara River Watershed.

The 2019 Yahara Watershed Academy (YWA) began on a very snowy February 12th. Snow started the evening of February 11th, with ten inches accumulating by the time the storm ended on the 13th. But the snow didn’t stop our group of students from learning about the Yahara River Watershed.

The YWA is made up of five day-long courses once a month, with students graduating in June. The Academy involves a partnership with the UW-Madison Nelson Institute for Environmental Studies and Edgewood College. Graduates will have received the knowledge and skills to become a network of informed leaders for our watershed.

Class began with introductions from the YWA leadership team and students. Students involved have diverse occupational backgrounds. There is a middle school science teacher, a geological engineer, a tree farmer, a technology CEO, an insurance site specialist, and more. Everyone in the YWA has interests or specializations in the environment and sustainability.

The February class activities included four formal presentations from professors and leaders in the community, as well as interactive group activities. Students also toured Madison Metropolitan Sewerage District (MMSD), and learned about its waste water cleaning process.

“One Water”

D. Michael Mucha, Chief Engineer and Director of MMSD gave the first formal presentation of the day. His presentation, “One Water,” discussed clean water and its importance, but also included a plethora of leadership advice.

Notable moments from “One Water”

Michael Mucha and water

“MMSD was formed 100 years ago because of drinking water. Septic systems around Lake Mendota were starting to pollute ground water and lake water. People wanted to save Lake Mendota to use as future drinking water.”

“When you flush the toilet, the water goes to MMSD to Badfish Creek to the Mississippi River to the Gulf of Mexico. It takes 40 days for water to get from MMSD to the Gulf of Mexico. We (MMSD) take each molecule of water, touch it, and make it right for wherever it goes next.”

“There’s a perception of purity when water comes in a bottle. That’s just good marketing.”

“Do things because you love the lakes. Not because you hate phosphorus. Deal with heart to approach a problem, instead of dealing with science or people’s heads.”

D. Michael Mucha

Michael Mucha and leadership

“As a watershed leader, are we solving the right problem? Keep asking this question to get to a root cause that’s manageable. This is how you solve problems.”

“As a leader, make sure you’re solving the problem in the right way. There’s a technical way and an adaptive way. It’s painful to lead because it doesn’t feel good. It’s easier to find a technical solution that everyone likes. To be a good leader, you need to push out and try things differently.”

D. Michael Mucha

“Yahara Watershed: A Place of Change”

Chris Kucharik is a professor in the Department of Agronomy and The Nelson Institute Center for Sustainabilty and Global Environment at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. His video documentary and presentation, Yahara Watershed: A Place of Change, sparked a thoughtful discussion. The discussion centered around our evolving climate in Wisconsin and its impacts on our lakes.

Lake Mendota’s history

We learned Lake Mendota once boasted white sand with water so clear you could see all the way to the bottom of the lakebed, even in areas of very deep water. Every year one millimeter of sediment accumulates on the lake bottom. The white sandy lake bottom is now covered in about one foot of “goopy” sediment.

Yahara 2070

Kucharik worked with other scientists on Yahara 2070. Yahara2070 is a report exploring what the Yahara Watershed may look like in the future. The report uses modeling to look at four different scenarios.

- Abandonment and renewal: what if the community isn’t prepared?

- Accelerated innovation: what happens if we prioritize technology?

- Connected communities: what if we shift our values?

- Nested watersheds: what happens if the community reforms governance?

Yahara 2070 continues to evolve as new challenges enter our watershed. New invasive species are arriving, and climate change is occurring. These variables may affect the biogeochemistry of our watershed, but we don’t know what those final consequences will be.

Glacial History of the Yahara Watershed

Another YWA presentation came from Elizabeth Ceperley, with the UW-Madison Department of Geoscience. She studies past climates and how climate changes have affected our landscape. We learned how the advance and retreat of ice sheets across the Midwest have transformed landscapes. In fact, Madison-area lakes formed as glaciers melted many millennia ago.

The evolution of Wisconsin’s landscape

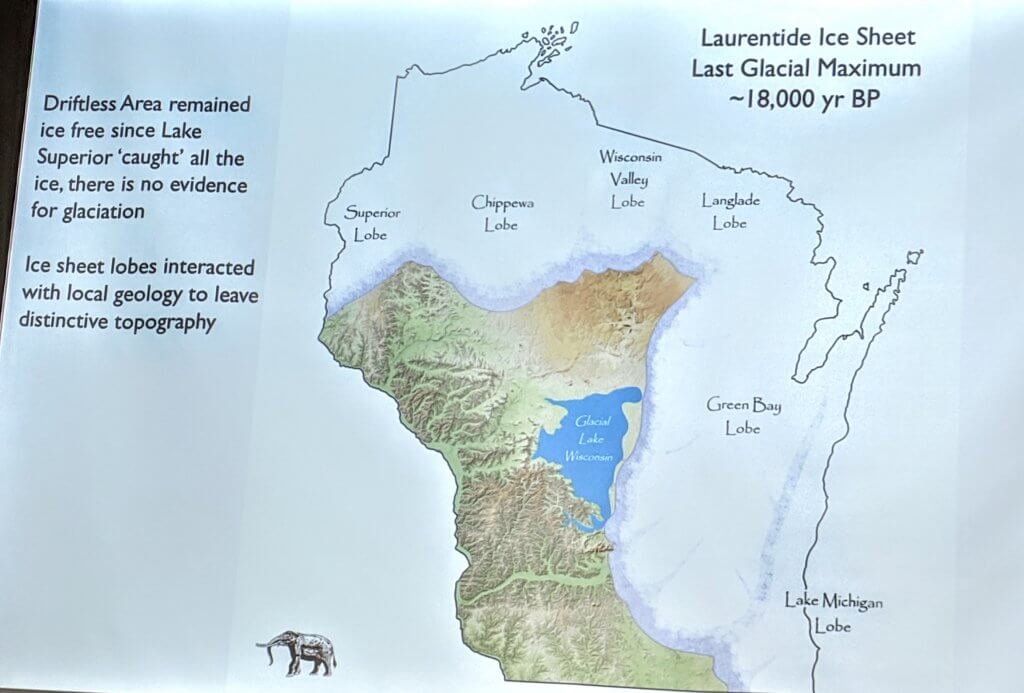

Ceperley taught the Yahara Watershed Academy about The Laurentide Ice Sheet, which was a massive sheet of ice covering North America. The thickest part of the ice sheet was located over Hudson Bay. As it grew, it expanded radially outward, advancing under its own weight. The last advance of the ice sheet took place 26,000 to 19,000 years ago. At that time, the ice sheet grew from the Arctic toward Madison.

The last glaciation left fingerprints on Wisconsin’s landscape, including our bedrock geology, the minerals left behind, and the dictation of our watersheds. In Dane County, we are at the very edge of where the ice sheet stopped. The Driftless Area of Wisconsin remained ice free, but eastern and northern sections of Wisconsin were covered in ice.

Topographical features of Wisconsin

If you travel through Wisconsin, you can still see topographical features left behind from the ice’s retreat. When Glacial Lake Wisconsin drained, it may have left behind the rock features near Wisconsin Dells.

We can find moraines left behind by the ice’s retreat. Moraines are made of till. Till is a sediment that has more than two grain sizes. It’s a mixture of silt, sand, pebbles, held together by clay. Elver Park in Madison is a moraine, featuring leftover boulders from the last glacial period.

We can also find drumlins in Wisconsin. Drumlins are elongated hills that look like half-buried eggs. Drumlins are oriented parallel to the ice flow and are made up of till. Have you been to Bascom Hill in Madison? That’s a drumlin!

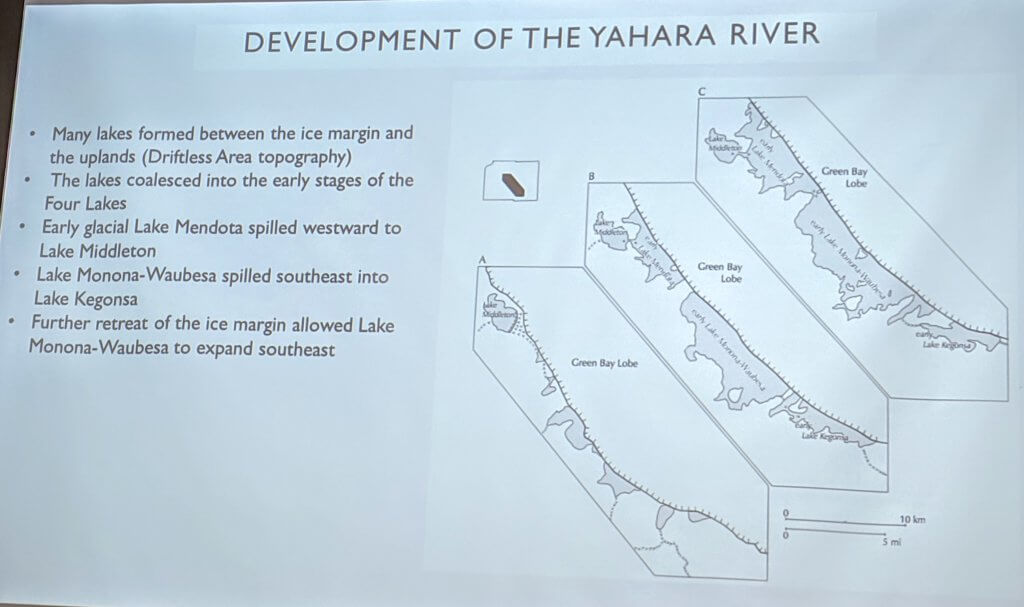

The Yahara River developed 18,000-14,000 years ago which was when the ice sheet reached its maximum. Glacial ice left Dane County around 13,000 years ago, leaving behind the lakes, soils, and geological features of our present day watershed.

“Water is sacred”

Ho-Chunk Tribe Elder, Andy Thundercloud, gave the final presentation of the day. He is a master language teacher for the Ho-Chunk Nation, he sits on the Ho-Chunk traditional court, he is a retired Physicians Assistant, a Badgers Football player from 1963, a Vietnam veteran, and appeared in a 2018 PBS documentary of Ho-Chunk Nation History.

Andy Thundercloud shared the oral tradition of the Ho-Chunk with the Yahara Watershed Academy. He spoke about how the earth, sun, moon, people, and our environment were created.

Thundercloud feels a connection to nature. He explains how the rocks, trees, and plants served as his protection during his time in Vietnam. He credits nature as the reason he was able to return safely from war.

“Everything has a spirit, even rocks.”

“We (Ho-Chunk Nation) revere the water. In one of our religions, there are offerings we make to the different spirits. We make an offering to the water spirit. We make an offering for its pureness and life-sustaining ability.”

“Water should be considered to be sacred by ALL of us! In my childhood, I never conceived of having to buy water. How long can we live without water? It isn’t very long. The same way with air. To me…to all of us…water should be sacred.”

Andy Thundercloud

Tour of MMSD

MMSD built a new maintenance facility in 2015 to provide more space and better working conditions for its employees. It is the first building on the campus to become LEED-certified, reaching a Platinum-level certification.

On the left are biosolids tanks, and on the right are aeration tanks.

Aeration tanks at MMSD

Air is added to the waste water in these tanks, and biological treatments are occurring. These tanks are the most energy-intensive part of the district.

“Toys of the underworld”

This bowling ball came through the sewer pipes and got stuck. MMSD finds all kinds of items that don’t belong with waste water. Oftentimes they see the toys children flush down toilets.

Struvite harvesting

Struvite is harvested in one of the buildings at MMSD. It is a calcium-like substance that clogs pipes. MMSD harvests the struvite and makes it into small pellets. Numerous bags are produced each week and sold to gardeners and farmers for fertilizer outside of our watershed.

Final tanks at MMSD

These are round tanks with a sweeping bar that rotates through the tank. Gravity allows final debris and solids to settle out in this location.

Ultraviolet treatment

An ultraviolet water treatment process takes place in the Effluent Building at MMSD. MMSD was the first water treatment facility in the country to use this process to clean its water in the 1980s.

Effluent Building at MMSD

Final discharge of the water takes place here. The water is released from here to Badfish Creek. From there, the water travels to the Mississippi River, and later ends up in the Gulf of Mexico.

There was plenty of great information and discussion throughout the first day of the Yahara Watershed Academy. We are looking forward to the March class, which will take place at the University of Wisconsin Arboretum. We will be learning about County efforts to improve water quality, limnology and the impacts of salt runoff, global and local climate change, sustainable agricultural practices, and more! Stay tuned to hear more about the March 2019 YWA class.

Find out more about the Yahara Watershed Academy.